fragments and reflections

Fragments & Reflections

2012 in review

The WordPress.com stats helper monkeys prepared a 2012 annual report for this blog.

Here’s an excerpt:

600 people reached the top of Mt. Everest in 2012. This blog got about 6,100 views in 2012. If every person who reached the top of Mt. Everest viewed this blog, it would have taken 10 years to get that many views.

Generosity in Scarcity

A little over a year ago, we received Sara* into our program at the Valley Community Center. She is now 8 years old and in the second grade. An only child, Sara lives with her parents, who are unofficially married, in the home of her paternal grandmother. Their home is in a neighborhood that is cut off from the rest of the city by the railways. Still, the family is fortunate to have electricity and running water.

Just last year Sara’s father was released from prison, where he had served a 3 year sentence for theft. Those three years were very difficult for Sara’s mother, who had never been to school, had no job, and was trying to care for Sara all by herself. Although her parents are now together, they are still unemployed and work odd-jobs when they manage to find them. From time to time, they receive some financial help from a brother who is working abroad. Otherwise, their only consistent income is Sara’s school stipend, which amounts to about $22 per month.

Just last year Sara’s father was released from prison, where he had served a 3 year sentence for theft. Those three years were very difficult for Sara’s mother, who had never been to school, had no job, and was trying to care for Sara all by herself. Although her parents are now together, they are still unemployed and work odd-jobs when they manage to find them. From time to time, they receive some financial help from a brother who is working abroad. Otherwise, their only consistent income is Sara’s school stipend, which amounts to about $22 per month.

One morning, a few weeks into this school year, Sara told her mother that she wanted to bring some money to the Community Center to give to the poor. Sara’s mother protested, asking, “What? Do you think we are rich?” Sara replied, “Yes, we have a house. There are other people that live on the street.” Since then, all of our second grade children decided to save half of their milk money every day in order to give to those in need.

One day, Bobby, another one of our second graders, took out his money to put in the donation box, while Sara registered the money in the notebook. It seemed that Bobby was struggling to live up to his commitment to be generous. Still, he put his money in the box. Lenutsa noticed this and praised Bobby for his sacrifice. But words were not enough for Bobby. He quickly turned to Lenutsa and asked, “Yes, but what about you?”

One day, Bobby, another one of our second graders, took out his money to put in the donation box, while Sara registered the money in the notebook. It seemed that Bobby was struggling to live up to his commitment to be generous. Still, he put his money in the box. Lenutsa noticed this and praised Bobby for his sacrifice. But words were not enough for Bobby. He quickly turned to Lenutsa and asked, “Yes, but what about you?”

The generosity, the sacrifice and the initiative of these children have challenged us. These kids live in dilapidated houses. Some of them are squatting in parts of abandoned buildings. Most have no running water or electricity. And yet they notice others with greater needs than their own. What is more, they want to help them.

Every day on their way from school to the Community Center, the  children pass by a family that is living in make-shift tents. The family was evacuated from their home after it was re-privatized and returned to its pre-communist owner. But since the family has nowhere else to go, they have set up camp in an open lot. Last week, the children took their collection of funds and decided together that they would help this family.

children pass by a family that is living in make-shift tents. The family was evacuated from their home after it was re-privatized and returned to its pre-communist owner. But since the family has nowhere else to go, they have set up camp in an open lot. Last week, the children took their collection of funds and decided together that they would help this family.

As they gathered the money and were preparing to go, Sara’s dad arrived early at the Center to pick her up. As Sara got her backpack and left to go home, she started to sob. Although her father is a pretty tough guy, he stopped to ask her what was wrong, but Sara was crying too hard to talk. So, he asked Lenutsa, and she explained what they had been planning. Sara’s father smiled and said he would wait.

Sara’s tears quickly dried, and the kids walked together to visit the homeless family. Sara was the spokesperson and asked them if there was a way that they could help. The grandmother, with weathered and wrinkled skin, said, “No one has asked us what we need or how they could help us.” Sara and her classmates took their money and bought some bread, cheese and cold-cuts. To protect the dignity of the family, Sara and Lenutsa returned by themselves to discretely give them the groceries.

This is a sample of the lessons of generosity that we are being taught by those living in scarcity. A child challenges the assumption that gift-giving is the privilege of the powerful and that the needy are objects of our philanthropy. Sara and her classmates show us that sacrifice and a shared commitment can become a profound gift that meets desperate needs and touches neglected hearts.

*Names have been changed to protect their identities.

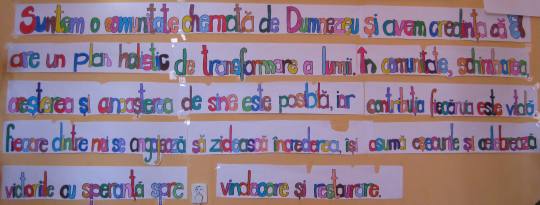

Nouă Paradigmă

În comunitatea Cuvântul Întrupat din România, am stabilit o paradigmă nouă, adică, o mentalitatea pe care o încercăm să realizăm. Necesită multă strădanie, dar lucrăm ca s-o implementăm. Aceasta este Nouă Paradigmă:

October Update from Galati

Resisting Fatalism

I sometimes find myself caught in the clutches of fatalism. I grew up in a family with an alcoholic father. Although he went through medical and psychological treatments, worked the Alcoholics Anonymous program, and managed to stop drinking for months and even years at a time, he is beaten by his illness. He is resigned to his addiction. And his resignation finds reflection in mine.

For the past 16 years, I’ve served among youth and adults with addictions – addictions to the streets, to gangs and to substances. While we’ve seen many of them come off the streets and some of them into healthy situations, a number of them are in jail, in hovels or on the streets. I feel like Lazarus’ sister, Mary, who went to Jesus and said, “Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died,” and Martha, who said, “‘Lord, already there is a stench because he has been dead for four days” (John 11:32, 39). Despite love, prayer, support and opportunities for change, we are watching our friends die in their addictions. I find myself being moved unwittingly by an undercurrent that says that people cannot change.

I also look at my own life and the changes that I hope for, pray for and work for but which, after years, I still don’t realize. The lack of change, of answers to prayer, of expected results all cultivates fatalism: no hope for the possibility of change. This reminds me of Albert Camus, a philosopher who deals with fatalism in many of his novels. In his book The Plague, Camus depicts the torturous disease that dominates people and over which they have no control. Camus’ character suggests that we resign ourselves to eminent death because we “… will [only] have suffered longer.”

The flicker of fatalism is fanned by society. Most of the public replies to the government with a defeatist sigh. They look at our environment and say, “That’s just Romania”. They look at the disenfranchised population among whom I serve and say, “Why waste your time and resources? They will never change. And if they do, they won’t amount to much. They were born into poverty, into a bad family, into dysfunction, and that’s where they’ll remain. That’s just the way they are.”

Of course, our kids, youth and families are raised and living in this very fatalistic society. Social psychologists, like Csikszentmihalyi and Seligman, affirm that helplessness is learned. Many of our kids lack any vision for the future other than what they see in their parents. There isn’t even a perspective which hopes for something different.

What is worse is that we witness fatalism creeping into the church. There I see mixed messages. Some overstress God’s determinism to such an extent that they make God responsible for sin and minimize any human freedom or responsibility. Others proclaim a prosperity gospel, which is a form of positive thinking that has no basis in reality. It is a positive fatalism, believing that certain determined effects follow certain human actions. On the other side of this unhealthy optimism is a millennial pessimism. Those that purport this view believe that things will get worse and worse and then the end will come with cataclysmic destruction. What is worse is that some think that they will be raptured to heaven and saved from the pain of the world, thereby relegating God’s passion for the redemption of creation and skirting any personal responsibility for the stewardship of creation. And even worse is that these bad theologies project fatalism onto the character of God.

These are the shackles of fatalism – a chain that binds the families I serve among, the society in which I live, and my own life. But I would concede to fatalism if I stopped here. There is an alternative, transformative vision for the history and destiny of humanity. There is a reality that breaks our despair.

This reality is God. God, who is Creator, has a plan for the renewal of all creation and refuses to let us go. It isn’t so much that I need to find resources of hope for God, for the world or for our kids; rather, I find that God himself hopes. God hopes for us. In the person of Jesus, God met fatalism and all its correlates at the cross, bringing fatalism to its end. In the resurrection and ascension, Jesus is the declaration, sign and execution of all God’s promises of healing, redemption and transformation. This is the Good News that snaps the chain of fatalism. And it is here that I am invited to live and hope. Our hopes are rooted in God’s.

This does not mean that we simply believe without acting. Ultimately, it means standing in the face of addiction, dependency, death, destruction. There we must either resign ourselves to these domineering finalities, or we must find grounds for hope. And that ground is God. We see that Jesus acknowledges death, destruction and decay. He experiences the weight of this finality, for example, in the death of Lazarus. Jesus wept (John 11:35). But God brings hope, the possibility of change, and even the possibility of the impossible. Jesus said with a loud voice, “’Lazarus, come out!’ The dead man came out, his hands and feet bound with strips of cloth, and his face wrapped in a cloth. Jesus said to them, ‘Unbind him, and let him go’” (John 11:43-44).

This is not hope that evades and avoids fatalism; rather, it addresses it head on. It is the hope that, with Abraham and Sarah, looks at our bodies and our possibilities and still hopes in God. That is, against possibilities for hope, still they hoped (Romans 5:18).

Hope isn’t something we always have at the start – a source that motivates us in the midst of trials. Rather, it is a result. St. Paul tells us that sufferings produce endurance, endurance produces character, and character produces hope (Romans 5:3-4). This is hope that is formed in the fire of pain and waiting and unfulfillment.

And this is the place where we must cultivate in the lives of our kids and their families, in our church and in our society. Although hoping hurts and although the things we hope for are not seen and often contradicted, we hope against hope in the promises of our Father in the Son and through the Spirit. Apart from the discipline of hoping against hope, I would also suggest two other actions.

First, we can pray. We pray for the things we hope for. In this way, the very act of prayer cultivates hope. In prayer we affirm our own powerless to transform and our faith that God can. Here I am reminded of the prayer attributed to Reinhold Niebuhr that is said at every Alcoholics Anonymous meeting:

God grant me the serenity

to accept the things I cannot change;

courage to change the things I can;

and wisdom to know the difference.

Second, in our communion with God our imaginations are infused with God’s dream for humanity and for creation. As ambassadors of Christ, we are called to give articulation to God’s dream. This is part of the prophetic office of the church. One way that this gift may be manifested is by affirming God’s dream and vision for those that are given over to fatalism.

Although this isn’t necessarily an example from within the church, the move The Cider House Rules depict such words of destiny spoken over children’s futures. It is a story of an orphanage – children that are abandoned and from the very early stages of life are in positions of disadvantage and despair. But every night as the children go to bed, the director of the orphanage tells them, “Goodnight, you princes of Maine, you kings of New England.” This is a prophetic vision that refuses the temptations of fatalism, opening up possibility and horizons to those who thought they had none.

We can affirm the destiny of the children and their families as being God’s creation and God’s beloved. We can affirm God’s plans of good and hope for every life. We can affirm life, wholeness, health and salvation in the face of fatalism. We can invite them to God’s dream and God’s hope for each one: Christ in you, the hope of glory!

Praying on October 1st

The Word Made Flesh community has traditionally set aside two days per month, the 1st and the 15th, to pray and fast for those who are vulnerable and in poverty, for our communities, and for the church.

This coming month on October 1st, we are setting the day aside to pray specifically for the Word Made Flesh communities. We are moving through profound transitions, and we are facing significant challenges.

We invite you to join us on this day of prayer. As we are able, we will post prayer points on our website www.wordmadeflesh.org. Here are a few for our community in Romania:

We invite you to join us on this day of prayer. As we are able, we will post prayer points on our website www.wordmadeflesh.org. Here are a few for our community in Romania:

Thanksgiving for:

– Our week of camp

– Our summer Discovery Team

– The 20 new kids in our Centers

– Our daily bread (we are able to serve about 50 meals per day)

– For the increasing involvement of the parents in the lives of their children

– Our community, friendships and mutual support

– The ways in which we see God working in the small ways in and beyond our community

– The enthusiasm and joy that the children bring

Praying for:

– Sensitivity to follow the movement of the Spirit

– The emotional healing of the children

– The physical healing of one of our boys who will have an operation on his lower intestine

– Wisdom and creativity to overcome our financial deficit

– We are launching a club for at-risk teens in our neighborhood. We are praying that the teens will acquire life-skills and positive values and that they come to the Lord and become part of the local congregation.

Prayer Update August

I know that this post is late. I realized that I sent it out via email but forgot to post it here. This was from August:

We are in the middle of a hot summer – and I am fully enjoying it! If you know me, you know that I struggle with anything below freezing, so I try and soak up the heat to get me through the cold winter.

We are in the middle of a hot summer – and I am fully enjoying it! If you know me, you know that I struggle with anything below freezing, so I try and soak up the heat to get me through the cold winter.

Our summer is also full of fun activities with the kids. During the school year, our activities revolve around the school schedules and their school work, but our major focus with the kids is not education but their personal formation. So, during the summer we are able to do more Bible studies and book studies, worship, therapeutic play, mentoring and discussions about skills they need for life. It’s a packed schedule, but it’s a lot of fun. We also have more time to play together: Settlers and Ticket-to-Ride, volleyball, and swimming. We were blessed to have some new friends, Nicholas and Autumn Morgenstern, do art and dance activities with the kids.

At the beginning of the summer, we received two first-grade girls into the Community Center. It is always a delight to see their excitement and the way that they experience things for the first time. We had wanted to receive another little first-grader as well, but the girl’s father decided to take her on a trip to France. For most kids that would be an exciting summer vacation, but for this little girl it most likely meant begging. Little beautiful girls are put on the street corners to ask strangers for money. And it can be quite lucrative. We are praying that this girl returns to Galati in time to start school. And we are hoping to receive her into our Community Center, where we can work to prevent child trafficking and forced begging.

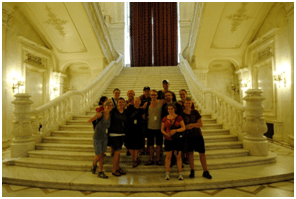

In June, we had a team of 12 come from George Fox University. We spent a week in Moldova and two weeks in Romania. The team did a lot to help us clean the Center, move furniture, cut down trees, rebuild fences. Member of the team also shared their testimonies with our youth, which was impactful. Of course, the team also did lots of fun activities with the kids. We really were encouraged and supported by them during our weeks together.

In June, we had a team of 12 come from George Fox University. We spent a week in Moldova and two weeks in Romania. The team did a lot to help us clean the Center, move furniture, cut down trees, rebuild fences. Member of the team also shared their testimonies with our youth, which was impactful. Of course, the team also did lots of fun activities with the kids. We really were encouraged and supported by them during our weeks together.

At the end of the summer, we are organizing our 12th annual camp. It will be a week when we can get out of the city and spend a full seven days together. Besides the archery, hiking and horseback riding, the kids will have 3 full meals a day and their own beds to sleep in. It costs us about $200 per child for the week. If you are interested in contributing to camp, please let me know.

will be a week when we can get out of the city and spend a full seven days together. Besides the archery, hiking and horseback riding, the kids will have 3 full meals a day and their own beds to sleep in. It costs us about $200 per child for the week. If you are interested in contributing to camp, please let me know.

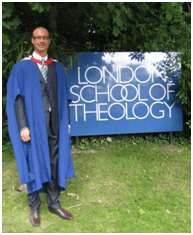

The last weekend of June, Lenutsa and I went to England – unfortunately, it wasn’t for the Olympics. Last October I finished up a MA course that I did through London School of Theology, and the graduation ceremony was held in June. It was a nice way to celebrate the achievement and to meet some of the other students and faculty. After the graduation, we visited some of our friends in Wolverhampton, where we spoke in some churches and small groups, and played in a golf fundraiser. As I hit a wapping 9 on the last hole (par 3), I was glad I could make everyone else feel better about their game. All in all, it was a jolly time.

The last weekend of June, Lenutsa and I went to England – unfortunately, it wasn’t for the Olympics. Last October I finished up a MA course that I did through London School of Theology, and the graduation ceremony was held in June. It was a nice way to celebrate the achievement and to meet some of the other students and faculty. After the graduation, we visited some of our friends in Wolverhampton, where we spoke in some churches and small groups, and played in a golf fundraiser. As I hit a wapping 9 on the last hole (par 3), I was glad I could make everyone else feel better about their game. All in all, it was a jolly time.

We are now in the U.S., in Omaha for most of August. We had the  privilege of meeting with friends at Winterset Community Church in Iowa. It was our first time there, and we were blessed by their welcome and worship. We will participate in the missions conference at Lifegate Church in Omaha. And we also hope to be with our friends at Emmanuel Fellowship before we depart. It is overwhelming and encouraging to be able to connect with those that have been praying for us and supporting us over the years and also to build new relationships that we pray will develop over the coming years.

privilege of meeting with friends at Winterset Community Church in Iowa. It was our first time there, and we were blessed by their welcome and worship. We will participate in the missions conference at Lifegate Church in Omaha. And we also hope to be with our friends at Emmanuel Fellowship before we depart. It is overwhelming and encouraging to be able to connect with those that have been praying for us and supporting us over the years and also to build new relationships that we pray will develop over the coming years.

As our ministry among the poor in Romania and our broader region of Africa and Europe continues to grow, we are looking for others to partner with us. Since I have been living and serving in Romania for more than 15 years, building new relationships with potential supporters has been a challenge. But this is essential if we are to continue to flourish. Please pray about partnering with us or in building partnerships for us.

Cemetery at the Margins of Galati

Our community practices remembering: remembering the forgotten, the marginalized and the lost. This past summer a group of students from George Fox University spent a few weeks serving with us. One afternoon we visited a cemetery on the periphery of our city where many of our kids have been buried. Sadly, many of their graves are no longer marked; some have been removed altogether.

Our community practices remembering: remembering the forgotten, the marginalized and the lost. This past summer a group of students from George Fox University spent a few weeks serving with us. One afternoon we visited a cemetery on the periphery of our city where many of our kids have been buried. Sadly, many of their graves are no longer marked; some have been removed altogether.

Margi Felix-Lund, one of the leaders of the summer team, wrote this poem:

God remembers…

…the birth of each child

the smiles & the tears

the injustice & the sorrow

the hope & the joy

God remembers the death of each child.

Although men & women may try

to wipe these children from the face of this planet-

although they may succeed in eradicating

the physical commemoration of their death-

these children, these vulnerable ones

will remain forever present

in the memory of God.

Roma, Romanians, Racism and Racial Differentiation

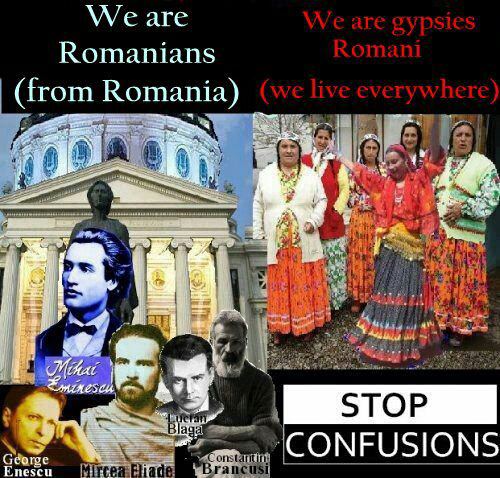

Since this image has been shared on facebook at least 9,200 times and multiplying, I thought I would respond. Along with the image is the “hope that there is no more confusion” about these two ethnicities. And “those of the opinion that Romanians should no longer be considered Gypsies,” then they should “share this picture wherever they can.”

Since this image has been shared on facebook at least 9,200 times and multiplying, I thought I would respond. Along with the image is the “hope that there is no more confusion” about these two ethnicities. And “those of the opinion that Romanians should no longer be considered Gypsies,” then they should “share this picture wherever they can.”

This message, it seems obvious to me, is racist. However, some think it’s simply a correct view of reality that doesn’t conform to the trends of political correctness. But I think that is a misunderstanding of “political correctness.” To be politically correct would mean that you, at least, adopt terminology like “Roma” or “Romani” rather than “Gypsy” or “Tigani”, which the Romani have rejected because of their derogatory roots and connotations. In this case, I don’t think we succumb to secular liberal ideology by using “Roma” or “Romani”; rather, it seems to me to be an opportunity to show a basic respect, or what Romanians call “bun-simt”. But I don’t want to die on the battlefield of politically correctness. I am willing, however, to fight against racism. This caricature is not simply politically incorrect, it is racist. Let’s walk through this:

1) To caricature the Romanians with 19th and 20th Century great males on one side but the Romani by females in traditional dress is full of denigrating undertones. If it were Romanians in traditional dress on one side and Romani in traditional dress on the other or Romani greats on one side and Romania greats on the other, that would be a step in the right direction.

2) Some have heard the Roma claim that these preeminent Romanians (Eminescu, Enescu, Brancusi, Blaga and Eliade) have Roma heritage. It isn’t unusual for various ethnicities to lay claim to great people. When I was studying in Moldova, I heard Russians laying claim to Eminescu. But I don’t hear those claims much from the Romani or from other Europeans. This is a straw-man argument; it doesn’t support the argument for ethnic differentiation.

3) With over 2 million Romanians spread across Europe, the US and Israel, it begs at least to nuance the affirmation that Romanians are from Romania and Romani from everywhere. There are millions of Romani from Romania. By stating otherwise, this caricature is false. Without any nuancing, the caricature is also racist.

4) It would also be helpful to nuance national identities and ethnic identities. Romani are nationally Romanian, and Romanian Romani are different than Romani from other nations. Additionally, there are many, many who are of mixed ethnicities (i.e. Romani/Romanian) in Romania. What is worse is that many “Romanians” with Roma ancestors deny their own history because of the dominant culture’s views of this marginalized minority – an attitude that amounts not only to the hatred of the other but also the hatred of one’s self.

5) This gets to larger problem with this caricature, which presents the “Gypsies” as the problem, and Romanians as good contributors to culture. If Romanians thought Gypsies were good, I believe that they wouldn’t be so offended when ethnicity and nationality are conflated. This cartoon is a rejection or exclusion of the other.

6) While I don’t paint the whole ethnicity with the same brush, I realize that there is a significant amount of criminal behavior by the Romani in western Europe that attracts the press and portrays the whole ethnicity and even nationality in a negative light. I decry the criminal behavior of Romani. But this can also be said of ethnic Romanians. I personally know dozens of Romanians who are involved in illegal activity in western countries, some of whom are now in jail, who attract the attention of the media. Just look at the area of cyber crime: http://www.news24.com/World/News/Romania-FBI-crack-down-on-cyber-crime-20111219 and http://www.fbi.gov/news/news_blog/u.s.-and-romania-targeting-organized-romanian-criminal-groups. To place the negative image of Romanians on the shoulders of the Romani is a way of scape-goating, and it is racist.

7) Some are upset that the Roma moved to western Europe in the 1990’s, told stories of persecution in Romania, and requested asylum. They were then seen as being “from Romania.” While I realize that many claims of persecution were false, we also need to recognize the places where persecution did occur. For example, Human Rights Report from attacks on Roma villages in the early 1990’s: http://dosfan.lib.uic.edu/ERC/democracy/1993_hrp_report/93hrp_report_eur/Romania.html

8) We also need to introduce historical factors into this discussion. Many Romanians, at best, do not know or, at worst, fail to acknowledge that the first evidence of Romani in Romania was in bills of sale as slaves. I would not promote the idea that contemporary Romanians are presently guilty of slavery or that they must atone for the sins of their ancestors, but I think we would do well to recognize the benefits we reap today by not having a heritage of slavery. The social conditioning that slavery and discrimination has on a people, as we see, is passed from generation to generation. And that is where I think we must share not in guilt but in responsibility for creating equity and inclusion in society.

9) As a Christian, it seems to me the issue is how do we live together and move together toward being what God intends us to be as a human family – without diminishing or confusing identities. If we want to differentiate ethnicities, there are healthier and more constructive ways of doing it.

Bowling Alone

Clint Baldwin led us in a discussion on bowling and social capital, based on Robert Putnam’s book.

Clint Baldwin led us in a discussion on bowling and social capital, based on Robert Putnam’s book.

Here is a summary:

Declining Social Capital – Trends over the last 25 years:

- Attending Club Meetings-58% drop

- Family dinners-43% drop

- Having friends over-35% drop

- Joining and participating in one group cuts in half your odds of dying next year.

- Every ten minutes of commuting reduces all forms of social capital by 10%

- Watching commercial entertainment TV is the only leisure activity where doing more of it is associated with lower social capital.

Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000)

by Robert D. Putnam

In a groundbreaking book based on vast data, Putnam shows how we have become increasingly disconnected from family, friends, neighbors, and our democratic structures– and how we may reconnect.

Putnam warns that our stock of social capital – the very fabric of our connections with each other, has plummeted, impoverishing our lives and communities.

Putnam draws on evidence including nearly 500,000 interviews over the last quarter century to show that we sign fewer petitions, belong to fewer organizations that meet, know our neighbors less, meet with friends less frequently, and even socialize with our families less often. We’re even bowling alone. More Americans are bowling than ever before, but they are not bowling in leagues. Putnam shows how changes in work, family structure, age, suburban life, television, computers, women’s roles and other factors have contributed to this decline.

America has civicly reinvented itself before — approximately 100 years ago at the turn of the last century. And America can civicly reinvent itself again – find out how and help make it happen at our companion site, BetterTogether.org, an initiative of the Saguaro Seminar on Civic Engagement at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government.

Here’s how to:

- Order (or review) the book at Amazon.com. You might want to order for your reading group, book club, class you teach or for your organization.

- Read excerpt of the book

- Find information on Prof. Robert D. Putnam

- Learn about efforts to help Americans reconnect, and how you can get involved, at BetterTogether.org, an initiative of the Saguaro Seminar on Civic Engagement at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government.

- Access the bibliography for the book.

- Access the data used in Bowling Alone, along with additional information not found in the book

- Listen to Prof. Putnam’s interview on NPR’s All Things Considered