fragments and reflections

Tradition

Building The New City: St. Basil’s Social Vision « In Communion

Building The New City: St. Basil’s Social Vision « In Communion.

The TAU Cross

The TAU cross, a common symbol of the Franciscan Order is encountered all over Assisi.

The TAU cross, a common symbol of the Franciscan Order is encountered all over Assisi.

In the year 1215, Pope Innocent III called for a great reform of the Roman Catholic Church – the Fourth Lateran Council. The Pope opened the Council by recalling the Old Testament image of the TAU as taken from the Prophet Ezekiel (9:4):

‘Go through the city, through Jerusalem, and put a mark on the foreheads of those who sigh and groan over all the abominations that are committed in it.’ (NRSV)

“We are called to reform our lives, to come into the presence of God as righteous people. God will know us by the sign of the Tau on our foreheads.” (Wycliffe)

Although the Pope was probably recalling the Hebrew text of Ezekiel from a Greek translation of the Bible, the allegorical imagery as taken from the two different sources, was powerfully significant all the same.

In Old Testament times the image of the TAU, as the last letter for the Hebrew alphabet, meant that we were admonished to be faithful to God throughout our lives, until the last. Those who remained faithful were called the “remnant of Israel,” often the poor and simple people who trusted in God even without understanding the present distress or hardship in their lives.

This symbolic imagery, used by the Same Pope who commissioned the Order of Friars Minor a brief five years earlier, was immediately taken to heart by Saint Francis, who was in attendance at the Fourth Lateran Council.

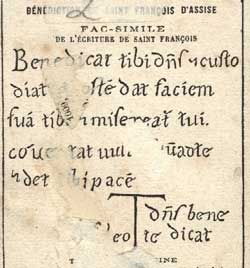

The TAU, shaped like the letter “T” in the Greek alphabet could easily be identified with the cross of Christ and therefore, instead of signing his name, Francis would use the sign of the TAU as his signature and he painted in on the walls and doors of the places where he stayed. It was a further external gesture of his complete immersion in the passion of Christ. Francis honored and embraced the TAU cross as a reminder of his Crucified Lord and of his love for us. He instructed them to not only let that serve as a reminder, but also as an active symbol for them to be a walking crucifix in their lives.

Saint Bonaventure in his Legenda Major 4-9 sees the connection between the text from the prophet Ezekiel and the mission of Francis: “…according to the text of the prophet, in signing the TAU on those men who cry and weep as a sign of their sincere conversion to Christ.”

Another connection of Francis with the sign of the TAU is his service to the lepers and the Brothers of St. Anthony the Hermit who administered the lazzaretos. From the 3rd century, St. Anthony is known for carrying the TAU cross and is often pictured as having a staff surmounted by a TAU and on their habit was sewn the emblem of the TAU. The TAU of the Antonians, servants of the lepers, reminded Francis of that special moment in his conversion when he embraced the leper and he was devoted to that symbol of the “love of Christ, who willed to be considered a leper for our sake” (Fioretti 25).

Today, followers of Francis, as laity or religious, would wear the TAU cross as an exterior sign, a “seal” of their own commitment, a remembrance of the victory of Christ over evil through daily self-sacrificing love. The sign of contradiction has become the sign of hope, a witness of fidelity till the end of our lives.

Crucea TAU

Crucea TAU este un simbol cunoscut în ordinul franciscan și, de aceea, este văzută peste tot în Assisi.

Crucea TAU este un simbol cunoscut în ordinul franciscan și, de aceea, este văzută peste tot în Assisi.

În anul 1215, Papa Inocent III a convocat o reformă majoră în Biserica Romano-Catolică prin Sinodul Lateran al patrulea. Papa a deschis Sinodul prin reamintirea imaginii TAU din Vechiul Testament, găsită în proorocul Ezechiel 9:4. Papa a spus, „Suntem chemați să ne reformăm viețile, să intrăm în prezența lui Dumenzeu ca fiind oameni neprihăniți. Dumnezeu ne va cunoaște prin semnul TAU care este semnat pe frunțile noastre”.

Ezechiel 9:4 – Domnul i-a zis: „Treci prin mijlocul cetăţii, prin mijlocul Ierusalimului, şi fă un semn pe fruntea oamenilor, cari suspină şi gem din pricina tuturor urîciunilor, cari se săvîrşesc acolo. (traducerea Cornilescu)

Ezechiel 9:4 – Şi i-a zis Domnul: Treci prin mijlocul cetăţii, prin Ierusalim, şi însemnează cu semnul crucii (litera “tau” care în alfabetul vechi grec avea forma unei cruci) pe frunte, pe oamenii care gem şi care plâng din cauza multor ticăloşii care se săvârşesc în mijlocul lui”. (traducerea bisericii ortodoxe române)

Cu toate că Papa folosea textul ebraic al lui Ezechiel pornind de la o traducere greacă a Bibliei, imaginile alegorice luate din cele două surse lingvistice diferite au totuși o semnificație puternică.

În Vechiul Testament imaginea TAU, fiind ultima literă din alfabetul ebraic, ne îndeamnă să fim credincioși lui Dumnezeu de-a lungul vieților noastre, până la sfârșit. Cei care au rămas credincioși erau numiți „rămășița din Israel”, de multe ori fiind oamenii săraci și simpli care s-au încrezut în Dumnezeu chiar atunci când nu înțelegeau strâmtorarea și greutățile prezente în viețile lor. Imaginea această simbolică, folosită de același Papă care a consacrat Ordinul Fraților Minori cu doar

cinci ani mai devreme, a fost preluată imediat de Sfântul Francisc care a participat la al patrulea Sinod Lateran.

TAU-ul, care are forma literei „T” din alfabetul grecesc, a fost identificat ușor cu crucea lui Cristos și, de aceea, de atunci, în loc să dea o semnătură, Francisc folosea semnul TAU-ului ca semnătură. De asemenea, a pictat-o pe pereții și pe ușile locurilor în care a stat. A fost un gest exterior al cufundării lui în pasiunea lui Cristos. Francisc a cinstit și a îmbrățișat crucea TAU ca o amintire a Domnului Răstignit și a dragostei lui pentru noi. Francisc i-a îndemnat nu doar să o ia ca o amintire, ci și ca un simbol activ pentru ca ei să fie un crucifix viu prin viețile lor.

Sfântul Bonaventure, în Legenda Majoră 4-9, vede legătura între textul din Ezechiel și misiunea lui Francisc: „conform textului proorocului, prin semnarea TAU-ului pe cei care plâng și jălesc ca un semn al convertirii lor sincere la Cristos”. O altă legătură cu Francisc și semnul TAU era slujirea celor cu lepră. La lazzaretos, unde slujeau frații Sfântului Anton Pustnicul, Sf. Anton, care în secolul 3 purta crucea TAU, este pictat cu un toiag încoronat cu un TAU și emblema TAU este cusută pe îmbrăcămintea fraților. TAU-ul fraților Antonieni, slujitorii celor cu lepră, îi aminteau lui Francisc de clipa aceea deosebită a convertirii lui când el a îmbrățișat un lepros și s-a devotat acestei imagini a „dragostei lui Cristos, care a voit să fie socotit un lepros de dragul nostru” (Fioretti 25).

Astăzi, urmașii lui Francisc, cei laici și cei religioși, poartă semnul crucii de TAU ca un semn exterior, un „sigiliu” al angajamentului lor, o amintire a biruinței lui Cristos asupra răului prin dragostea care se sacrifică zi de zi. Semnul contradicției a devenit un semn al speranței, o mărturie a fidelității până la sfârșitul vieților noastre.

Franciscan Revolution and Renewal (part 3)

As I mentioned in the last post, another important revolutionary reform that still affects the church today is the basis for individual rights.

The idea of individual or subjective rights arose from the social conceptions of feudalism. The landholders had ‘rights’ which were coextensive with their ‘dominion’. These were not only individuals. Not only barons, but monastic secular chapters, city corporations and guilds, all with their estates, asserted their several rights and looked to royal and papal government to uphold them.

The idea of individual or subjective rights arose from the social conceptions of feudalism. The landholders had ‘rights’ which were coextensive with their ‘dominion’. These were not only individuals. Not only barons, but monastic secular chapters, city corporations and guilds, all with their estates, asserted their several rights and looked to royal and papal government to uphold them.

But the Franciscans subverted the grounding of subjective rights in property. Through their commitment to poverty, the mendicants, though owning nothing, could still eat and drink and claim the necessities of life. They grounded subjective rights on the ‘right of natural necessity’ (Bonaventure) or on a ‘right of use’ (Ockham). Thus, individual rights were claimed by a broader segment of society.

Although rights were dissociated from real property, as O’Donovan points out, these subjective rights still carried proprietary overtones. Gerson invoked the term ‘dominion’ to describe this right of self-preservation, and, indeed, initiated the tradition of conceiving freedom as a property in one’s own body and its powers.

It is not difficult to see the trajectory from the Franciscans to liberation or feminist theologies. But even to these post-modern movements, Francis has a prophetic witness as Francis based his subjective right in God’s affirmation of his person, body and power. His path or relinquishment and renunciation for the sake of others challenges any claim to rights for oneself without the other.

Franciscan Revolution and Renewal (part 2)

The Porziuncula is a good symbol of Francis’ revolutionary impact on the church – though the word “revolutionary” might not be the most precise. Contrary to revolutions that change regimes or constitutions, Francis led a revolution of the identity and essence of the church. And because this revolution happened in and with the church, it may be better called a “reform.” Two important revolutionary reforms that still affect the church today are the basis for authority and the basis for individual rights.

The Porziuncula is a good symbol of Francis’ revolutionary impact on the church – though the word “revolutionary” might not be the most precise. Contrary to revolutions that change regimes or constitutions, Francis led a revolution of the identity and essence of the church. And because this revolution happened in and with the church, it may be better called a “reform.” Two important revolutionary reforms that still affect the church today are the basis for authority and the basis for individual rights.

Drawing on Augustinian thought about the ‘two cities’ and on the Aristotelian influence regarding the ‘nature-grace’ duality, medieval theologians spoke of two distinct realms that wield authority: the sacral (spiritual) and the political (secular). The church held that spiritual authority (for example, theories and claims to justice) had to have priority over secular authority (for example, the application of justice).

In Francis’ day, the basis of authority for both realms was property. In the sacral realm, the Pope, it was claimed, owned all property, not ‘in particular’ but ‘universally’; we might say, all property rights that others exercised were grounded in his authority. The chain of equivalences that legitimized authority went like this: property meant power; power meant jurisdiction; jurisdiction meant authority; and authority meant a determinative role for the church in shaping society under the law of Christ (O’Donovan, The Desire of Nations, 206).

Franciscan friars confronted Papal authority with the possibility of absolute poverty. This provoked some intense questioning of what it meant to possess ‘spiritual authority’. The threat which the Franciscans posed to current doctrines of the papacy was far more serious than that vague discomfort which poverty always poses to wealth. By vowing to poverty, Francis subverted the traditional claims to authority, which risked unraveling the whole garment of Christian society.

Out of the long controversy came an attempt to articulate a different concept of spiritual authority, one based on the authority of the word. This was the work of the imperialist theologians who took up the Franciscans’ cause. Their role was, of course, ambiguous, serving at the same time the church’s interest in recovering a truly spiritual authority and the secular rulers’ interest in having an uncontested field. Their most important contribution lay in the principle that a word of Gospel truth has its own distinct authority, different from the authority of threat or command (O’Donovan, The Desire of Nations, 207). In this, it is easy to identify Francis’ influence on the Reformation.

Of course, today the authority of the word is debated and contested. Retreating to modern propositional stances and risking fideism, the church attempts to root its authority in the infallibility word of the Pope (Roman Catholic), the inerrant word of the Bible (Protestant) or the infallible word of Tradition (Eastern Orthodox). And those outside the church attempt to root authority in the doubting subject (Descartes) or “erase” any claim to authority altogether (Derrida). Francis points to a different way. In his commitment to absolute poverty, he detaches intrinsic authority from extrinsic power. He grounds authority in love, dependence and brotherhood rather than domination, coercion and prestige. Authority is offered, not imposed. It speaks to Augustine’s notion of authority as “trustworthy.”

Ultimately, the authority promoted by Francis was not rooted in word but in God, God who communicates to humanity not only in human language but also in human flesh. He who, though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness. And being found in human form, he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death—even death on a cross. Therefore God also highly exalted him and gave him the name that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bend, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue should confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father (Philippians 2:6-11).

Francis grasped that this high authority, as Jesus shows us, is revealed at the bottom. Following this authority, Francis sold his possessions, begged his bread, and, with the stigmata on his hands and feet, he died naked on the ground at the Porziuncula.

Pilgrimage: Following Itineraries or Maps?

A couple of weeks back, Lenutsa and I, along with Sarah Lance, Walter Forcatto and Chris and Phileena Heuertz, had the opportunity to take a pilgrimage to Assisi, Italy. This little medieval city is the place where two of the church’s great saints, Francis and Claire, lived out their vocation of prayer, poverty and love for God. Although these two remarkable Christians lived 800 years ago, their calling, lifestyles and faithfulness have been inspirational and challenging to the Word Made Flesh community. One of my hopes in making this pilgrimage to Assisi was to connect more with this movement of God, this radical spirituality, and its revitalizing effects in the church and for the world.

A couple of weeks back, Lenutsa and I, along with Sarah Lance, Walter Forcatto and Chris and Phileena Heuertz, had the opportunity to take a pilgrimage to Assisi, Italy. This little medieval city is the place where two of the church’s great saints, Francis and Claire, lived out their vocation of prayer, poverty and love for God. Although these two remarkable Christians lived 800 years ago, their calling, lifestyles and faithfulness have been inspirational and challenging to the Word Made Flesh community. One of my hopes in making this pilgrimage to Assisi was to connect more with this movement of God, this radical spirituality, and its revitalizing effects in the church and for the world.

As I was preparing for my first steps on this pilgrimage, I came across a fundamental distinction in how we have conceived “space” in history: itineraries and mapping.

Mapping is a relatively recent development in human history. It is a modern idea that followed the rise of the nation-state (see Michel de Certeu’s The Practice of Everyday Life). In pre-modern times principalities did not have clearly defined borders and often had landholdings within other principalities. Nation-states, however, needed to identify their borders and employed the technology of mapping to serve its cause. Maps are static, two-dimensional abstractions of space. Mapping means homogenization and delineation, often arbitrarily, for the sake of identity and control. Mapping is a form of will to power, particularly power over space. Yet, mapping cannot account for the temporality of space. The only thing “temporal” in mapping is its claims to permanence.

Mapping is a relatively recent development in human history. It is a modern idea that followed the rise of the nation-state (see Michel de Certeu’s The Practice of Everyday Life). In pre-modern times principalities did not have clearly defined borders and often had landholdings within other principalities. Nation-states, however, needed to identify their borders and employed the technology of mapping to serve its cause. Maps are static, two-dimensional abstractions of space. Mapping means homogenization and delineation, often arbitrarily, for the sake of identity and control. Mapping is a form of will to power, particularly power over space. Yet, mapping cannot account for the temporality of space. The only thing “temporal” in mapping is its claims to permanence.

In pre-modern times space was not conceived through maps; rather, it was understood through itineraries. Itineraries depict a storied-space (see William Cavanaugh’s Theopolitical Imagination). They tell of sites, steps and experiences that one takes as they travel and as they make pilgrimage. They prescribe actions, prayers and places to sleep for different points along the journey. Where mapping imposes onto space the dominant story, the story of and for the nation-state, itineraries are purely local and particular. They are stories that emerge from the earth by its different smells and tastes, its rocks and its fruits. These stories are not merely told; they are performed.

(It was interesting to see no billboards in Assisi, which evidently are not allowed so as to keep its medieval appearance. It was even difficult to find an internet connection! The only way that the dominant stories, like McDonald’s, could smuggle their message in was on the sides of taxis that moved in and out of the city – that itself was a sad commentary on the contrast and aloofness of the dominant culture from the Franciscan story. I found the absence of the dominant narratives to be fitting to a place that celebrates Franciscan spirituality. And it is an example of how the soft prophetic voice of Franciscan spirituality continues to speak to our contemporary world.)

(It was interesting to see no billboards in Assisi, which evidently are not allowed so as to keep its medieval appearance. It was even difficult to find an internet connection! The only way that the dominant stories, like McDonald’s, could smuggle their message in was on the sides of taxis that moved in and out of the city – that itself was a sad commentary on the contrast and aloofness of the dominant culture from the Franciscan story. I found the absence of the dominant narratives to be fitting to a place that celebrates Franciscan spirituality. And it is an example of how the soft prophetic voice of Franciscan spirituality continues to speak to our contemporary world.)

Itineraries are stories anchored in steps. Where mapping excludes the temporal, itineraries incorporate it. Space is not measured with metrics but rather with hours or days. Itineraries are written for boots, not jet-engines. At each step we are invited to follow in the footsteps of former fellow travelers, tracing a narrative through space and time. To see the same hills and valleys, to hear the same songs of the birds, and to experience the same gift of place. Itineraries tell of brooks and wells, of hotels and hospitality. Maps identify place, itineraries experience place.

Whereas mapping excludes the strangers and forcibly “settle” the pilgrims in order to define, protect and extend its borders (see Phyllis Tickle’s “Forward” to Phileena Heuertz’s Pilgrimage of a Soul), itineraries are invitations to strangers and to pilgrims to experience the generosity of locals.

Refusing borders and dominating narratives of space, the pilgrim follows the itineraries of pilgrims forgone. But the experience of each pilgrim takes its own shape. The itinerary is prescriptive but not coercive. The itinerary is an invitation. Taking the journey means crossing and even subverting borders and a dominant narrative about space. In this way, the practice of pilgrimage is a practice of resistance. It cultivates a life that resists the illusion of control, the exclusion of the stranger and the domination of people and places. Itineraries mean transforming the places on the map into alternative spaces filled with alternative lives and alternative lifestyles marked and orientated by our pilgrimage to the City of God.

As I made pilgrimage through Assisi, I reflected on the trajectory that Claire and Francis charted. They created a new storied-space, and they invited the likes of me to journey through it. But although their story was new, it too was not original. In the homes, barns and businesses that Francis’ and Claire’s lives transformed into “alternative spaces,” they all link the stories of the saints to the story of Christ. They were misunderstood, rejected, persecuted and poor and yet joyful, loving and generous. Claire and Francis were “saints” inasmuch as they imitated Christ. Their stories were original in that only they could live out their own stories as only I can live out mine. But they draw from the church’s tradition and are told against its background. They chart the itinerary and further enrich the tradition, which now comprises the background for my pilgrimage. O, to follow Claire and Francis, to walk faithfully and to fill each place with stories about our radical love for God!

As I made pilgrimage through Assisi, I reflected on the trajectory that Claire and Francis charted. They created a new storied-space, and they invited the likes of me to journey through it. But although their story was new, it too was not original. In the homes, barns and businesses that Francis’ and Claire’s lives transformed into “alternative spaces,” they all link the stories of the saints to the story of Christ. They were misunderstood, rejected, persecuted and poor and yet joyful, loving and generous. Claire and Francis were “saints” inasmuch as they imitated Christ. Their stories were original in that only they could live out their own stories as only I can live out mine. But they draw from the church’s tradition and are told against its background. They chart the itinerary and further enrich the tradition, which now comprises the background for my pilgrimage. O, to follow Claire and Francis, to walk faithfully and to fill each place with stories about our radical love for God!