fragments and reflections

Spirituality

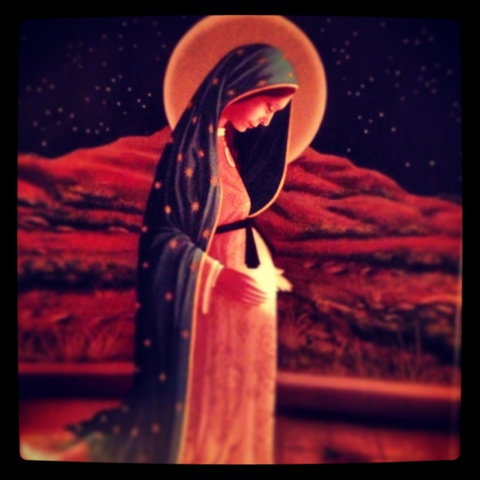

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, God Is In the Manger

“No powerful person dares to approach the manger, and this even includes King Herod. For this is where thrones shake, the mighty fall, the prominent perish, because God is with the lowly. Here the rich come to nothing, because God is with the poor and hungry, but the rich and satisfied he sends away empty. Before Mary, the maid, before the manger of Christ, before God in lowliness, the powerful come to naught; they have no right, no hope; they are judged. …

“Who among us will celebrate Christmas correctly? Whoever finally lays down all power, all honor, all reputation, all vanity, all arrogance, all individualism beside the manger; whoever remains lowly and lets God alone be high; whoever looks at the child in the manger and sees the glory of God precisely in his lowliness. …

“And that is the wonder of all wonders, that God loves the lowly … God is not ashamed of the lowliness of human beings. God marches right in. He chooses people as his instruments and performs his wonders where one would least expect them. God is near to lowliness; he loves the lost, the neglected, the unseemly, the excluded, the weak and broken.”

“I believe that God can and will bring good out of evil, even out of the greatest evil. For that purpose, he needs men [and women] who make the best use of everything. I believe that God will give us all the strength we need to help us to resist in all times of distress. But he never gives it in advance, lest we should rely on ourselves and not on him alone. A faith such as this should allay all our fears for the future.”

What Do We Mean by “Evangelism?”

Word Made Flesh presently ministers in nine countries where we live among the poor and long to communicate the Good News of King Jesus and His coming Kingdom. Typically, the term we ascribe to this activity is “evangelism.” But as we minister among the poor, we wrestle with the limitations and follies of our traditional understanding of the concept.

The word “evangelism” often conjures in the contemporary mind images of televangelists, traveling preachers or zealous proselytizers. When we define evangelism, we usually talk about “getting people saved” or “making sure you know where you are going when you die.” Although we do long for people to come to know God and to have eternal security, this view is a narrow and truncated form of biblical evangelism. Such a view creates a gospel that is mere word, void of content. It secularizes and domesticates the gospel, which constrains it to the private realm and withdraws from social and political sin. It turns the gospel into a consumer product by aiming to satisfy the individual’s needs while lacking the commitment to transform humanity. This gross individualism has mutilated our concept of evangelism and fed the atomization of humanity and society.

This faulty understanding, propagated by many American evangelicals, has been successfully exported to evangelical churches around the world. Consequently, when telling our fellow Christians that we evangelize, some think we’re only talking about biblical paper dolls moving across flannel boards or PowerPoint presentations. Worse yet are the unsatisfied frowns we often see when explaining that we do not simply evangelize through our words. Therefore, we want to take this opportunity to reflect on the meaning of biblical evangelism so that our concept and practice of mission may be radicalized.

We must ask ourselves what biblical evangelism is, and how the tradition of the church can correct our currently deviated understanding. The word “evangelism” is derived from the Greek euangelion, “good news, gospel, evangel.” Likewise, “evangelization” means “to announce the good news.” However, since the early 19th century, church and mission circles have changed and increasingly distorted the meaning of the verb “evangelize” and its derivatives (David Bosch, Transforming Mission). In this article, we will attempt to outline an understanding of evangelism as differentiated from contemporary definitions and in line with its original meaning.

Evangelism is often described as the proclamation, presence, persuasion and prevenience of the gospel. Let us outline each of these aspects of evangelism, then look at their implications.

Evangelism is Proclamation

Evangelism is proclamation, but it is not synonymous with verbiage. It is helpful to distinguish between euangelion (gospel) and kerygma, the Greek word that refers to preaching or proclaiming that which is fundamental and all-embracing in the New Testament. Kerygma was the event of being addressed by the word. Some have suggested that there was a particular kerygmatic formula about Jesus—that is, the “language of the facts,” and the facts being that God came in Jesus Christ, was crucified, resurrected and ascended. But evangelism cannot be reduced to verbalizing the Good News. Proclamation from the pulpit or mass-media tends to be a monologue, detached from relationship. Evangelism that is reduced to only proclamation is extremely individualistic. It often leads people to an interior repentance that is merely felt or pondered in thought without becoming real repentance (See Jon Sobrino, Christology at the Crossroads).

Biblical evangelism is personal. The Word was made flesh. The gospel was embodied in the person of Jesus. That is why the expression “gospel” is used in the New Testament to refer both to the apostolic proclamation of Christ and to the history of Christ. The gospel is the message; the gospel is also the life of Jesus. In Christ, the message and the messenger are indivisibly one. Jesus desires to disclose Himself; He is the Evangelist in that He continually is communicating and drawing humanity into dialogue with God. He communicates personally to persons, and He commissioned persons to continue communicating personally.

To evangelize is to communicate this joy; it is to transmit, individually and as a community, the good news of God’s love that has transformed our lives (Gustavo Gutierrez, A Theology of Liberation).

Therefore, the proclamation must be made in relationship and in the power of the Spirit. Paul says, “For our gospel did not come to you in word only, but also in power and in the Holy Spirit and with full conviction” (1 Thess. 1:5).

Evangelism is not just proclaiming otherworldliness. Either to justify the status quo or to anaesthetize our inability to change it, we often preach about the “pie in the sky.” Of course, we do believe and proclaim the wonderful day when God will consummate His creation, when justice and righteousness reign, and when God’s people dwell forever in His presence. But God wants us to experience abundant life even now. He wants us to experience the in-breaking of His presence and to participate in the anticipatory celebration. Jesus invites us to pray: “Let Your Kingdom come on earth as it is in heaven” (Matt. 6:10). An overemphasis on otherworldliness causes us to detach ourselves from creation and from history. Consequently, evangelism does not speak about the promises for creation, that God will make all things new, nor does it seriously confront historical sins. That is why it is important to remember that we do not emancipate ourselves from history altogether, but we take the past promises of God up into our hopes of the future consummation as disclosed by the gospel (Jürgen Moltmann, The Church in the Power of the Spirit).

The other side of otherworldliness is this-worldliness. But evangelism is not synonymous with the gospel of progress or any other socio-political movement. The martyred Archbishop Oscar Romero pointed out,

The danger of reductionism as far as evangelization is concerned can take two forms. Either it can stress only the transcendent elements of spirituality and human destiny, or it can go to the other extreme, selecting only those immanent elements of a kingdom of God that ought to be already beginning on this earth (Voice of the Voiceless).

Unfortunately, human projects have identified themselves as the coming Kingdom of God. Much of modern mission has piggybacked on the colonization of the world by Western powers. The message of the gospel of Jesus Christ was adulterated with the promises of Western culture, which assumed itself to be better and more advanced. Often in the name of civilizing, the church transplanted a foreign god and a foreign religion that not only failed to keep its promises but also actually led to cultural regress (See Jonathan J. Bonk, Missions and Money). The gospel cannot be identified with any cultural, social or political movement. In fact, it must confront and challenge them (Mortimer Arias, Announcing the Reign of God; Lesslie Newbigin, The Gospel in a Pluralistic Society). True evangelism is Good News. It rings true in an indigenous environment because the people exist through the Word (John 1:3) and because the Spirit has already been there preparing the hearts of the people (Rom. 2:15).

Evangelism is Presence.

Evangelism is presence but needs explication. The gospel is not only declaratory; it is performatory. It can be the first because it is the second (Newbigin, The Gospel in a Pluralistic Society). The presence of the gospel is of particular importance today as we are flooded with words, yet often experience the powerlessness of language. We know that our “actions speak louder than words,” that our lifestyles “speak for themselves,” and that a message is validated by its medium. The people of God embody, explain and are the living interpreters of the gospel. A Romanian Orthodox missiologist, Ion Bria, said, “[Evangelism] is not only oral proclamation of the gospel but also martyrdom (martyria), the following in the steps of the crucified Christ” (The Liturgy after the Liturgy). Martyria means “witness.” First we witness through our lives and deeds, then we explain what happened. For example, Jesus’ witness to the Kingdom provoked those around Him to ask questions. Who is He that even forgives sins? Who is this Jew that receives a drink from a Samaritan? Who is this Prophet that dines with sinners? The gospel, then, is an answer to the question that a person or a people is asking (Newbigin, The Gospel in a Pluralistic Society). Jesus’ example shows that evangelism does not only mean that we “go and tell”; it also means that we witness through the work and lifestyle of the Christian community, provoking questions to which the Good News of Jesus Christ is the answer (Myers, Walking With the Poor).

In our affirmation of evangelizing through presence we must also recognize that this aspect has received current favor by many because we have lost confidence in the Truth—which if it is true, compels us to proclaim it. The Good News is entrusted to us. If we fail to proclaim it, we are unfaithful stewards. The gospel must be explicit. Though we often like to quote St. Francis of Assisi who said, “Preach the gospel and use words when necessary,” we must also realize that he did use words and many heard the Good News and many came to the Lord. In fact, he preached to a Muslim sultan, who invited him because he had heard of St. Francis’ lifestyle. Peter exhorts us to live such a lifestyle:

Keep your behavior excellent among the Gentiles, so that in the thing in which they slander you as evildoers, they may on account of your good deeds, as they observe them, glorify God in the day of visitation (1 Pet. 2:12).

Evangelism is Persuasion

Evangelism is persuasion, but not peddling or proselytizing. Persuasion is convincing people of the gospel through apologetics2. Paul said, “Knowing the fear of the Lord, we persuade men” (2 Cor. 5:11). But evangelism is not selling or enticing people to buy a marketable product. Paul said, “For we are not like many, peddling the word of God, but as from sincerity, but from God, we speak in Christ in the sight of God” (2 Cor. 2:17). The Indian theologian Vinay Samuel is fond of saying that evangelism is a commitment to sharing, not an announcement of expected outcomes (Myers, Walking With the Poor).

Evangelism means persuading people, but it does not mean proselytizing them (See Lesslie Newbigin, Signs Amid the Rubble). Evangelism does not mean making converts—though that is a desired result—or adding members to our club. Many times, we find ourselves struggling with feelings of guilt because there seems to be no tangible “fruit” from our ministry. At other times we find ourselves tempted to tell other Christians what they want to hear: “… we just saw another one come to the Lord,” “… he has been coming to church on his own accord for a few months now,” or “… she is starting to pray at mealtimes.” These remarks may bring a few pats on the back, but only serve to propagate the misconception about “successful” evangelism.

When we place exclusive emphasis on the winning of individuals to conversion, baptism and church membership, numerical growth of the church becomes the central goal of mission. Then seeking justice and peace are separated and relegated to the margins of the church’s mission. Over the last century, much of the church has defined its failures and successes by numbers. If the church was growing numerically, it was successful; if not, it was failing. Though a growing church may be a sign of God’s life and work, this predisposes us to value the size more than the persons. Just as the ideology of the Industrial Revolution turned humanity into a cog in the machinery of society or an item on the assembly line of productivity, so the ideology of modern church success has turned humanity into a donor resource and community into church membership. This is not simply evangelism misconstrued; it is anti-evangelism because at its core it dehumanizes.

If Jesus is the model Evangelist, then we must let the cross be the critique of evangelistic success. At the cross, those persuaded by Jesus’ ministry either betrayed Him or went into fearful hiding. At the cross, there were no supportive crowds, no grandiose church buildings and no tally of the day’s converts. “Successful” evangelism is faithfully testifying to the crucified God, who died to preach the Good News to a lost and confused world; the attestation of successful evangelism is the Resurrection. This understanding puts the indication of success not in the response of the evangelized but in the obedience of the evangelist.

Evangelism is not an activity for non-believers only, because Christians never cease to need evangelism. Avery Dulles reminds us that evangelism is not complete with the first proclamation of the gospel: “It is a lifelong process of letting the gospel permeate and transform all our ideas and attitudes” (Cited in Bryant Myers, Walking With the Poor). This creates space for our worship, discipleship and spirituality to be evangelistic. This also frees us from our “savior complex” and releases conversion and salvation to God. As the song joyfully affirms: “Salvation belongs to our God, who sits on the throne, and to the Lamb” (Rev. 7:10).

Evangelism is the Prevenience of the Spirit

Evangelism is the prevenience of the Spirit, not simply the activity of the Christian missionary. It is not enough to speak of the proclamation, presence and persuasion of the gospel; we must also recognize the prevenience or the previousness of the Spirit (Lesslie Newbigin. The Open Secret). That is to say that long before the Christian arrives with the Good News, the Spirit of God has been moving, preparing and wooing humanity to Himself. Evangelism participates in and flows from God’s previous activity.

Implications for Life and Ministry

This brief analysis of evangelism as proclamation, presence, persuasion and the Spirit’s prevenience has many implications for our lives and ministries. We learn that evangelism is holistic, not fragmented. Holistic ministry is an approach to mission that considers the whole of humanity without compartmentalizing it, the whole of society without atomizing it, and the whole of the cosmos without categorizing it. Each day the WMF community welcomes hundreds of children in our lives and homes around the world. This welcoming includes shelter, advocacy, education, the sharing of meals and discipleship. We minister to the whole child—mind, soul and body. We also minister to the families of these children. We do not isolate them from their society or from their world but try to bring transformation within it.

In his book Good News and Good Works, Ron Sider attempts to work out an understanding of doing evangelism and doing social action without confusing the two tasks. Sider defines evangelism as leading a person to become a personal disciple of Christ while arguing for social action as transforming social and political structures. He tries to preserve the integrity of evangelism by not confusing it with social action and vice-versa. Although Sider does affirm that the separate activities are inseparable, Vinay Samuel criticizes him for being dualistic. Samuel argues that we cannot be “dualistic evangelicals who think it is possible to come to Christ and not be engaged in social justice” (Chris Sugden, Seeking the Asian Face of Jesus). Because the evangelism is holistic, we cannot divide its parts. When Jesus brings the child, the outcast and the weak into the center of society, justice is done and the Good News is proclaimed. When, in the name of Jesus, street children learn to read and write, eat healthy meals and are protected from police brutality, the Good News is proclaimed.

Evangelism is transformational. Christ’s announcement of the coming Kingdom of God included community building, confrontation and intentional conflict, liberation, hope, repentance and the forgiveness of sins, persecution, healing, miracles and discipleship. Biblically, we are not called merely to supply a different interpretation of the world, of history and of human nature, but to transform them in expectation of a divine transformation (Jürgan Moltmann, A Theology of Hope).

Evangelism, for Christ, was transformation. This transformation influenced the whole of society and the whole of humanity. It demanded a response, either total acceptance or total rejection.

Biblical evangelism finds its basis in a proper Kingdom-of-God understanding. This Kingdom understanding requires total submission to the all-encompassing nature of this Kingdom. Such submission touches on every aspect of living, being and doing.

Evangelism is an announcement. The New Testament theologian N.T. Wright searches biblical history to learn what evangelism meant for Jesus and the apostles. He states, “The gospel is for Paul, at its very heart, an announcement about the true God as opposed to false gods” (What Saint Paul Really Said). Whether it is to the god of money, the god of sex, or the god of power, the gospel of the Kingdom announces the end to false gods, and their reordering and consummation into a new Kingdom. Wright likens evangelism to Caesar’s herald, who proclaims the royal announcement. The herald would not say, “If you would like to try to have an experience of living under an emperor, you might care to try Nero.” Rather, the herald’s proclamation is an “authoritative summons to obedience—the obedience of faith.” The Gospel of God is not an alternative to other gods, but it is the heralding of the Kingdom by which all others will be judged. The Apostle Paul writes, “The gospel is the power of God for salvation” (Rom. 1:16). Wright comments, “The gospel is not just about God’s power saving people. It is God’s power at work to save people.” Evangelism, therefore, is the announcement that the crucified and risen Jesus is Lord.

This New Testament understanding of evangelism has deep implications on our practical ministry. We can no longer understand evangelism as mere words. We can no longer hold evangelism in one hand and social justice in the other while claiming that we are faithful to biblical evangelism. We can no longer democratize evangelism by submitting it to public opinion for its acceptance. Instead, we must acknowledge the totality of biblical evangelism: Jesus is Master of all, will be all in all, and is turning the kingdoms of this world on their heads.

Correspondingly, evangelism is a denouncement. When we announce the totality of Jesus’ lordship, we simultaneously denounce any opposition to His reign. Gustavo Gutierrez says that the church must make the prophetic denunciation of every dehumanizing situation, which is contrary to fellowship, justice and liberty. The truth of the gospel, it has been said, is a truth which must be done” (A Theology of Liberation).

Walter Wink says that “evangelism is always a form of social action. It is an indispensable component of any new ‘world’” (Naming the Powers). That is to say that the Good News engages and challenges persons, societies, structures and the cosmos. We fully realize that only persons can repent and receive Christ, but persons are social beings within social structures, and the gospel announces the lordship of Christ over the whole cosmos, including its society, structures and systems. Wink goes further to affirm that “social action is always evangelism, if carried out in full awareness of Christ’s sovereignty over the Powers.” Although there needs to be more than a simple awareness of Christ’s lordship for this statement to be true, it certainly shows our need for a paradigmatic change in our understanding of evangelism. “Jesus did not just forgive sinners, He gave them a new world” (Wink). If this is true, then we rule out the idea that evangelism and social action are two separate segments or components of mission.

David Bosch explains that evangelism is mission, but mission is not merely evangelism. Thus, these terms should not be equated. Bosch, in a very detailed examination of evangelization and mission, shows that evangelism must be placed in the context of mission. Each context demands that the gospel addresses its particular predicaments: injustice, corruption, abortion, murder, greed, gluttony, drug abuse, etc.

Evangelism that separates people from their context views the world not as a challenge but as a hindrance, devalues history, and has eyes only for the “nonmaterial aspects of life” … What criterion decides that racism and structural injustice are social issues but pornography and abortion personal? Why is politics shunned and declared to fall outside of the competence of the evangelist, except when it favors the position of the privileged society? (Bosch, Transforming Mission).

Could it be that we have re-defined evangelism to suit our own lifestyles and forfeited biblical evangelism because it is too radical? Biblical evangelism is Jesus’ Good News to the poor, imprisoned, crippled, deaf and blind; biblical evangelism is Jesus’ invitation to follow Him and to become His disciples; biblical evangelism is Jesus’ call to service in the reign of God; biblical evangelism is a call to mission.

Paul exhorts us in 2 Timothy 4:5 “to do the work of the evangelist, fulfill your ministry.” From the aspects discussed in this article, it is easy to see how our ministry will reflect our understanding of the meaning of evangelism. We must unlock the shackles of our contemporary definitions and seek to know God’s intention for evangelism. He is calling us to announce the Good News through proclamation, presence, persuasion and the promised prevenience of the Spirit. This means we must denounce anything that opposes the gospel; we must be holistic and transformational in our evangelism; and we must do evangelism in the context of mission.

Our hope is that we lay our ideas and misconceptions before Jesus, where they can be transformed and radicalized. Jesus is the Gospel made flesh. He is the embodiment of the Good News. He is the point where the evangel and the evangelist are one. Our prayer is that by His Spirit, we may be Christ’s heralds, announcing the coming of the new heaven and the new earth, and that the Good News of the Father would truly be Good News to the world.

The Atheism of Believers

By definition, atheism is the denial of God, a belief in the inexistence of God or the inability to believe in God. There are private atheists and militant atheists. (Personally, I have the same lack of patience for militant atheism as I do for militant fideism.) Yet, atheism doesn’t seem to be an option or a desire for most of the world’s population. Having traveled and lived in places where there is no hope except in a primordial cry for help – even in the face of that cry not being answered. This cry is an act of faith, of hope and of belief. So, while I do sympathize with protest atheism that protests the existence of God in an evil world and especially evil that is done in the name of God, I view atheism as a luxury made possible by individualistic cultures that see faith as a choice among other options and that desacralize and disenchant the world.

But it is relatively easy for people of faith to bash atheists, when we should recognize our own wrongheaded atheism. Let’s look at this oxymoron: believer’s atheism. The creation narrative found at the beginning of the Jewish Scriptures tells us that human beings are created in the image of God. Human beings – all of them – bear God’s image and likeness. The implication is that when we do not acknowledge the image of God in others, then we are practicing a different kind of atheism. Paradoxically, some atheists confer dignity to others – even to their enemies, while many so-called believers refuse. The believers’ atheism is most visible in their isolation from the poor, in their rejection of the stranger and immigrant, and in their inability to create space to relate to their enemies.

Being created in the image of God signifies a solidarity with all humanity. Through this basic dignity and vocation, God has offered us space to relate to one another – especially when we have fundamental disagreements with one another and are tempted to reject, hate and abuse.

So, we are called to a new kind of faith. We are called to denounce atheism that doesn’t believe in God’s image. And we are invited to believe in and to honor God by helping the poor, receiving the stranger and loving our enemy.

Building The New City: St. Basil’s Social Vision « In Communion

Building The New City: St. Basil’s Social Vision « In Communion.

Vulnerability, Children and the Image of God – part 2

In part 1 of the post “Vulnerability, Children and the Image of God,” I outlined humanity’s imaging God through vulnerability and difference rather than through power. I follow Jensen’s book Graced Vulnerability. What I am attracted to in Jensen’s depiction of vulnerability as expression of image of God is that it speaks of a status rather than of an activity like rationality, dominion, etc. But this line of thought may be accused of begging the question unless we describe how humanity, as imago Dei, is distinguished from the rest of creation which also is marked by vulnerability and difference.

I don’t have a fully-worked-out answer to this. At the moment, this is where I am at: When thinking of human beings in the image of God, we usually have an individualistic framework. We can justify our individualism with Genesis 1 – God created humankind in God’s own image – and then finding in Genesis 2 a solitary man. But individualistic readings are subverted by the same text: So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them (Genesis 1:27). The image of God is a collective identity, not individualistic. If image of God is a collective, speaking of humanity rather than a solitary human being, then humanity’s representation of God is not the life of solitary individuals. This provides space for the exercise of rationale, stewarding, and multiplication without denying the image of God in those without abilities to rationalize, steward or multiply. What is more, is that understanding imago Dei as vulnerability means that rationale, stewardship and multiplication are directed towards and used on behalf of those that are most vulnerable.

I don’t have a fully-worked-out answer to this. At the moment, this is where I am at: When thinking of human beings in the image of God, we usually have an individualistic framework. We can justify our individualism with Genesis 1 – God created humankind in God’s own image – and then finding in Genesis 2 a solitary man. But individualistic readings are subverted by the same text: So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them (Genesis 1:27). The image of God is a collective identity, not individualistic. If image of God is a collective, speaking of humanity rather than a solitary human being, then humanity’s representation of God is not the life of solitary individuals. This provides space for the exercise of rationale, stewarding, and multiplication without denying the image of God in those without abilities to rationalize, steward or multiply. What is more, is that understanding imago Dei as vulnerability means that rationale, stewardship and multiplication are directed towards and used on behalf of those that are most vulnerable.

So, along those lines, I’m thinking about image of God as an ontological designation. God designs/designates humanity as God’s image. It is who humanity is, not what humanity does. This would be compatible with some Orthodox theology that states that humanity participates in the material (animal) world and in the spiritual (angelic) world. That seems to me to be an ontology that is all-inclusive, especially of those so vulnerable that they do not have capacities to perceive or act on their own behalf. Yet, while the participation of humankind in the material and spiritual spheres differentiates humanity from the rest of creation, we are still placing too much weight on humanity’s distinction from the rest of creation. Rather, humanity as image of God must be based on correspondence to God. The correspondence is rooted in God’s designation of humanity as God’s image. The designation of humanity at Creation then leads us to Incarnation. God as human being affirms the divine correspondence with humanity (without dissolving divinity into humanity). And the glimpses of the revelation of God in the womb and of God on the cross affirm the ideas of image of God as vulnerability and difference. In Jesus we have the invitation to be fully human, imaging God through vulnerability, which is received more than achieved, as described in Philippians 2:5-11 – “Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness. And being found in human form, he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death – even death on a cross” – without succumbing to the serpent’s and Babel’s grandiose temptations of power “you will be like God” (Genesis 3:5).

So, along those lines, I’m thinking about image of God as an ontological designation. God designs/designates humanity as God’s image. It is who humanity is, not what humanity does. This would be compatible with some Orthodox theology that states that humanity participates in the material (animal) world and in the spiritual (angelic) world. That seems to me to be an ontology that is all-inclusive, especially of those so vulnerable that they do not have capacities to perceive or act on their own behalf. Yet, while the participation of humankind in the material and spiritual spheres differentiates humanity from the rest of creation, we are still placing too much weight on humanity’s distinction from the rest of creation. Rather, humanity as image of God must be based on correspondence to God. The correspondence is rooted in God’s designation of humanity as God’s image. The designation of humanity at Creation then leads us to Incarnation. God as human being affirms the divine correspondence with humanity (without dissolving divinity into humanity). And the glimpses of the revelation of God in the womb and of God on the cross affirm the ideas of image of God as vulnerability and difference. In Jesus we have the invitation to be fully human, imaging God through vulnerability, which is received more than achieved, as described in Philippians 2:5-11 – “Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness. And being found in human form, he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death – even death on a cross” – without succumbing to the serpent’s and Babel’s grandiose temptations of power “you will be like God” (Genesis 3:5).

This is an attractive notion of image of God in which humanity affirms and accepts this correspondence to God as a grace, designation and invitation. It also removes any ideas being gods in the world – ideas that have deluded the powerful throughout history and delude us today – and actually dehumanize and mar the image of God. Against the power-brokers: we image God by simply being, and we let God be God.

Simplicity as Acceptance, Challenge and Beauty

We often think of simplicity in terms of minimizing, down-sizing, and reducing what we consume. One of the precepts that we cite regularly are the words of St. Elizabeth Ann Seton: “We live simply so that others may simply live.” But simplicity means much more than this.

Simplicity is a fundamental acceptance of our human condition. It is the acknowledgment of an existence that is, to use a phrase from the Book of Common Prayer, “earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust.”

Simplicity is also a confrontational critique and denunciation of the idolatry of wealth. Jesus lovingly said to the wealthy young ruler: “You lack one thing; go, sell what you own, and give the moneyto the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; then come, follow me” (Mark 10:17-27). These words inspired the Desert Fathers and Mothers and the later monastic tradition to leave everything to pursue God. By practicing simplicity we stand in the long tradition of faithful Christians who recognized the demonic potentialities of possessions and refused complicity with their lure and their lies.

Simplicity doesn’t only deconstruct wealth; it is also constructive. Simplicity aims to create beauty. We actually find the beauty of simplicity throughout society. It is the beauty of God’s ordered creation, which resonates in us when we experience health, justice, salvation and life.

Simplicity doesn’t only deconstruct wealth; it is also constructive. Simplicity aims to create beauty. We actually find the beauty of simplicity throughout society. It is the beauty of God’s ordered creation, which resonates in us when we experience health, justice, salvation and life.

While beauty is most obvious in art and literature, where the artist pursues aesthetics in symmetry, tone and coordination, it is also evident in sciences. For example, the 2012 Nobel Prize winners in economics are praised for creating something beautiful, as their work results in better patient care and education. Dorothy Wrinch’s molecular theory is called by our contemporaries a “beautiful vision” because it takes the complexities of data and gives a simple explanation. Likewise, in the domain of physics, scientists call Einstein’s theory of relativity “elegant”. ![]()

However, the aesthetic character of simplicity isn’t always easy to see. For example, I have had the opportunity to visit a particular monastery carved out of the hills in Moldova. In the bottom of a cave is a chapel, and at the entrance to the chapel sits an old monk. Most of the time, he sits alone. It is cold. He prays. His austere life looks harsh and unattractive. But it is beautiful for those with eyes to see. The beauty radiates from his wrinkled face in his love, joy and quest for God. Simplicity is seen in the singularity of his desire to seek and love God.

Simplicity is a spirituality, a way of being in the world, and, as with any healthy lifestyle, it requires discipline and cultivation. Whenever I feel like I’m making some progress in my walk with the Lord, it seems I’m always confronted with something that opens my eyes to new profundity.

This happened on a recent visit to our community in Sierra Leone. I woke up one Sunday morning hurrying to get ready for church. I said a short prayer to ask God for energy for the day and wisdom for the activities before me. Our spirituality is reflected in our prayers.

We arrived at church and began the singing, clapping and swaying. The sister leading worship shouted a prayer: “Thank you that I am not dead.” I was cut to the quick, challenged and convicted by her prayer of boisterous gratitude, her petition for life in the midst of poverty, and her joy in the immediacy of salvation. It wasn’t that my prayer was bad or wrong, but it limped in its motivation. My prayer was an option, a choice, a luxury. My Sierra Leonean sister’s prayer was a necessity. It was a real prayer for daily bread, for the Father to provide life. For if the God of Life didn’t, who would?

The challenge for me is to move from a spirituality of luxury to a spirituality of simplicity. I am invited to embrace my human condition and be grateful in dependence and need for the Father’s life-giving love and provision. Through the practice of simplicity, we unmask the false promises of wealth for power and security. With singularity of purpose, we seek to know and love God. And, in the midst of the difficult and harsh realities of the world, we practice simplicity that is recognized for its beauty. Following her example of a spirituality of simplicity, we take up the charge of Mother Teresa: “Now let’s do something beautiful for God.”

Pantocrator

The word Pantocrator is of Greek origin meaning “ruler of all”. Christ Pantocrator is an icon of Christ represented full or half-length and full-faced. He holds the book of the Gospels in his left hand and blesses with his right hand.

The word Pantocrator is of Greek origin meaning “ruler of all”. Christ Pantocrator is an icon of Christ represented full or half-length and full-faced. He holds the book of the Gospels in his left hand and blesses with his right hand.

The icon portrays Christ as the Righteous Judge and the Lover of Mankind, both at the same time. The Gospel is the book by which we are judged, and the blessing proclaims God’s loving kindness toward us, showing us that he is giving us his forgiveness.

Although ruler of all, Christ is not pictured with a crown or scepter as other kings of this world. The large open eyes look directly into the soul of the viewer. The high curved forehead shows wisdom. The long slender nose is a look of nobility, the small closed mouth, the silence of contemplation.

It is the tradition of the Church to depict “God is with us” by having the large Pantocrator icon inside of the central dome, or ceiling of the church.

Henri Nouwen “the Beloved” – part 8

These sermons was formative for me and for all of us in Word Made Flesh. I will post it in 8 parts:

Henri Nouwen “the Beloved” – part 7

These sermons was formative for me and for all of us in Word Made Flesh. I will post it in 8 parts: