fragments and reflections

Church

misiune si migrare

Acest video este de la Societatea Cersetorilor tinuta la biserica baptista “Sfanta Treime” despre misiune si migrare:

For Mission or For Church? – A Question about the Future of the Lausanne Movement

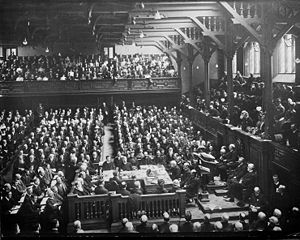

As we approach the one-year anniversary of the Lausanne Congress in Cape Town, I thought I’d share some thoughts on the church’s participation in the Lausanne Movement. At the event, there were about 4,000 participants from 198 nations. The goal was to have the participants represent the demographic of global church leaders. Although women, as a percentage of the global church, were underrepresented, the ethnic representation was quite diverse. I was impressed by the constant possibility to listen, to encourage and to build relationships across broad swaths of the church.

As we approach the one-year anniversary of the Lausanne Congress in Cape Town, I thought I’d share some thoughts on the church’s participation in the Lausanne Movement. At the event, there were about 4,000 participants from 198 nations. The goal was to have the participants represent the demographic of global church leaders. Although women, as a percentage of the global church, were underrepresented, the ethnic representation was quite diverse. I was impressed by the constant possibility to listen, to encourage and to build relationships across broad swaths of the church.

However, Andy Crouch noticed that another particular group was underrepresented. In his article for Christianity Today entitled ‘Unrepresented at Cape Town’, Crouch observed that of the four thousand delegates participating at the Third Lausanne Congress in Cape Town, the prominent figures from evangelical churches in the U.S. were underrepresented. Crouch speculates that their absence is due to these “important” leaders’ decision to use their power and time elsewhere. From his observation, Crouch extrapolates implications on power, influence, innovation and the future of global evangelical movements. While I would agree with some of Crouch’s analysis, I think that the absence of “western” Church leaders is not simply a matter of their deciding how they use with their influence and their limited time; rather, it points to a deeper problem inherent in the Lausanne Movement. It reveals a division in the Lausanne Movement between traditional “sending” countries and traditional “receiving” countries, and it indicates a misguided division between church and mission.

The West and the Rest

The inception and development of the Lausanne Movement has had the primary goal of engaging those outside the church through mission and evangelism. Many of the signatories and proponents of the Lausanne Covenant were churches interested in global mission, missionary agencies and para-church organizations.

The inception and development of the Lausanne Movement has had the primary goal of engaging those outside the church through mission and evangelism. Many of the signatories and proponents of the Lausanne Covenant were churches interested in global mission, missionary agencies and para-church organizations.

However, as missionaries and evangelists established churches in these “unreached” locations, many of the new churches adopted the Lausanne Covenant as a statement of faith. The Lausanne Covenant was an intrinsic part of their make-up. Moreover, as churches networked, evangelical alliances and federations used the Lausanne Covenant as a basis for their organizations.

The result from these historical developments is that churches from the so-called “west” view the Lausanne Movement as relevant for outreach and primarily for cross-cultural mission while the rest of the global evangelical church understands the Lausanne Movement as a central statement of faith and a basis for ongoing church development.

So, I don’t think “western” evangelical church leaders were absent because they were not interested or because the Cape Town Congress was trumped by other priorities. Rather, I suspect that “western” church leaders do not view Lausanne as relevant to their church ministry. If my suspicion is true, a sad corollary is the cloaked patronization that our “western” churches, perhaps unwittingly, communicate: “We think that the Lausanne Movement is good for you, but we don’t need it.”

This, I think, is the real issue regarding the use of power – and not merely the access to the public platform, as Crouch supposes. The power of the “western” churches is the ability to do it alone. The “western” churches can afford to have their own individualized statements of faith and to choose whether or not they develop local partnerships. While these choices and individualistic stances are simply wrongheaded, in places where churches are a minority or where they have few resources, they are also luxuries. What is worse is that this use of power divides rather than unites the global church.

Church and Mission

Recognizing that the traditional “missionary-sending” churches appeal to the Lausanne Movement for its “missionary” activity but not for its “church” activity helps to identify an underlying theological problem. Namely, there is a rift between “church” and “mission”. Thinking that there is “mission” for those outside of the church and “church” for those inside the church is a mistake. Mission is the action of God through the Church. The Church is the Body of Christ, empowered by the Spirit to be the Father’s witnesses in the world. The church is missional, and mission is ecclesial.

Of course, this division between “church” and “mission” has been identified by many like Brunner, Newbigin and Bosch. What we see today in the lack of participation by “western” church pastors in the Lausanne Movement is a very concrete social manifestation of this theological error.

Unity through the Lausanne Movement

Although the divisions between the traditional “sending” churches and the traditional “receiving” churches and between conceptions of church and mission pose problems for the Lausanne Movement, the Lausanne Movement is in a unique position to ameliorate these divisions.

Lausanne can begin by naming these divisions as a problem. Lausanne can continue bringing churches together, including traditional “receiving” churches but especially traditional “sending” churches. Lausanne can help the “western” churches learn from the missional churches in the “non-west” to develop missional perspectives and activities in their local church contexts. They can also help the “western” churches understand that the Lausanne Movement is not simply a mission movement but a church movement, and they can build relationships between local churches in the “west” and local churches throughout the world.

Likewise, Lausanne can facilitate the “non-western” churches in working with “western” churches to send missionaries not only into the local communities, cities and villages but also into trans-geographic contexts.

The Lausanne Movement can also facilitate the development of a more robust theology of missional churches and ecclesial mission.

By recognizing and mediating these divisions, the Lausanne Movement can support not only the church’s engagement in the world but also mediate healing and development within the global church. The church’s power can serve to bring us together. The church’s resources can be shared more effectively. The global church can become more united. And, at the end of the day, the Lausanne Movement itself will be a more credible representation of the global church.

Christian Ministry as a Contributor to Poverty?

While we may be good intentioned, full of compassion, and desiring everyone’s salvation, we Christians may unwittingly keep people in poverty. Here are a few ways this happens:

- In some instances, we hold a reductionist understanding of the Gospel. We seek to save the soul, while disregarding the body. We give people a message of salvation that includes a prayer for forgiveness without giving them a community that helps them in their hunger and need. We provide a spiritual solution for physical problems. Conversely, we may use their bodies to reach their souls. We offer food and assistance so that they listen to and respond to our message of salvation. But this often leads to Rice Christians: those that respond to manipulation with manipulation, responding to the thin messages of salvation in order to satisfy their present needs.

- Sometimes we patronize the poor. We have experienced something that we know everyone needs. But when we try to give to others, we aren’t always postured as receivers. We assume that we know their problems, and we come with the solution. Although we may not understand the cultural and social dynamics of the marginalized communities, we come with solutions that have worked in our communities. Moreover, we treat the marginalized as our projects and our mission objectives rather than as people and precious relationships.

- In some circles, Christians promote a skewed understanding of blessing. We affirm that God’s blessing is evidenced by wealth and prosperity. We tell the poor that if they come to a proper relationship with God, they will be blessed, and this blessing will lift them out of their poverty. Those that preach this gospel assume that their own material status is a sign of God’s favor. Those that do not rise in status are presumably not living in proper relationship with God. Although this message is highly attractive to the poor, it primarily serves the preachers of this gospel at the expense of their audience.

- Sometimes we disempower the poor. We may come with aid and inadvertently destroy vulnerable small businesses in the community. Or we may offer our charity without taking responsibility. This happens when we give money to charities that help poor factory workers while purchasing cheap clothing made in those factories. The other side of this is when we offer charity without developing responsibility. When people are treated like donation receptacles, they become dependent on charity and lose a sense of responsibility for what they receive.

When the Gospel doesn’t address the whole person but just their “spiritual” needs, the poor are left hopeless in their poverty, thinking that God is either baiting them through their physical needs or unconcerned in this life with their physical plight.

When we patronize the poor, the vulnerable are further marginalized, exploited and objectified.

When we promote a skewed understanding of blessing, we create discontent and guilt. Worse, we paint a picture of a god that relates to and through the wealthy, relegating the poor as cursed.

When we disempower the poor, we keep them in their poverty, subordinated to our “generosity” and numbed in their dependence. By giving charity we may quiet our conscience without addressing the structural causes of poverty.

Negotiating Citizenship: Nonviolent Resistance

In pre-modern times, empires would give citizenship rights to vassal countries that paid the empire its dues. This practice continues today, albeit in different forms. Yesterday, the Romanian President visited Washington D.C. to sign a missile defense treaty. The U.S. military will build an anti-missile system in Romania and will station 500 U.S. troops in Romania. In exchange for this agreement and for Romania’s participation in the war in Afghanistan, Romania is asking for a visa waiver for its citizens to travel to the U.S. For military alignment, Romania wants some of the benefits of citizenship in the empire.

To counter and critique this militaristic basis for citizenship, those with citizenship in heaven commit to loving those on the other side of the missile ‘defense’ so that we may share together in the citizenship of heaven. Although we may lose the benefits of the empire by not participating in its claims to protect through violence, we know that the empire ultimately cannot deliver on those claims.

Those with heavenly citizenship resist battling with flesh and blood and name, unmask and engage the powers and principalities that dehumanize, oppress and kill those created after the image of God.

Negotiating Citizenship

A country always calls its people to be good citizens. This commitment to citizenship trumps all other allegiances.

A country always calls its people to be good citizens. This commitment to citizenship trumps all other allegiances.

We see this in American Christians who do not differentiate between being a Christian and American but rather equate being Christian with being American. We fly American flags in our sanctuaries, support our troops, and encourage Christians to support the Constitution and to obey the laws.

The fact that the commitment to one’s nation is the paramount obligation is even more evident in the national discourse on American Muslims. At every turn, Muslims are asked to prove that they are “good” Americans, which they do by affirming the Constitution, their belief in freedom and democracy, their participation in and sacrifice for the military, and their fidelity in paying taxes. But the burden of proving their American-ness is constantly on their shoulders – and the shoulders of other non-White and non-Christian citizens.

In the ancient Greco-Roman world, citizenship was even more a privilege than it is in our democratic countries, and just a small portion of the population was citizens. Only males qualified for citizenship. You could not be a slave. Most were land owners. The Greco-Roman society was structured around its citizens, who were the Pater Familias, around whom other family members, servants, slaves and beneficiaries had their livelihoods and status.

Although cities were allowed to have their own civic religions, the emperor demanded utmost allegiance to himself. A good citizen was loyal to the king. Interestingly, one of the purposes of Josephus’s history of the Jews is to demonstrate that Jews are good Roman citizens.

In the early Church, there are also Christian claims to being good citizens. For instance, some speculate that Luke’s description of the Jerusalem church in Acts 2 and 4 depicts the ideal Greek notion of society.

However, most Christians were not citizens but rather, as Peter says, “strangers and aliens.” The early Church spoke about having their citizenship in heaven. Although they were not given citizenship in the kingdoms of this world, early Christians asserted their citizenship in the heavenly city. Today, I often hear interpretations of heavenly citizenship as being one’s passport to heaven. But for the early Church, heavenly citizenship was not so much about one’s eternal destination as it was a different basis for living in the present world. This citizenship shaped one’s convictions and actions. This citizenry was a place of belonging and social identity for the excluded and oppressed, particularly, for women, slaves, and non-property owners.

When the Church is later accepted and authorized by the Roman Empire, the distinction between Roman citizenship and heavenly citizenship is diluted. How did the Church respond? Many of the Church Fathers defended Christians as “good” citizens but still challenged the claims of the empire. Others renounced the privileges of the empire and lived in solitude or in small communities on the fringes of the empire, committing themselves to celibacy, poverty and other ascetic disciplines.

Usually, the ascetic commitments to celibacy, poverty and obedience are viewed as a reaction to the world’s dominant temptations of sex, wealth and power. While this is true, this view usually fails to see the social implications. Patlagean points out that these ascetic commitments redefined citizenship. The ascetic commitments challenged the foundations that shaped traditional identity: marriage, family and property. To be a “good” citizen in this new vision of society meant to choose poverty, celibacy, and ascetic generosity. This meant that relationships were based on freedom rather than power, on chastity and equality rather than progeny and misogyny, and on generosity rather than competition.

When I look at the vision of the early Church for a new society and its citizenry, I am challenged to renegotiate the places in which I commit to country and the places where I must resist its demands. I am challenged to re-evaluate my commitments to the state in light of my ultimate allegiance to my citizenship in heaven.